The 137-mile Altamaha River is one of the great natural treasures of the eastern United States. Pronounced Al’ta’mahaw’ the river starts at the confluence of the Ocmulgee and the Oconee Rivers near Hazelhurst and flows undammed to the Atlantic Ocean in Darien. Crossed by roads only five times, the largely undisturbed river is believed to be more than 20 million years old, and pumps an average of 100,000 gallons of fresh water into the sea every second, making it the third largest contributor of fresh water along the eastern seaboard. The river at Doctortown Landing near Jesup is a broad, meandering stream, surrounded by cypress, gum, and willow swamps. Set back up to 2 miles from the main channel are ancient bends of the river, isolated by time into curved, oxbow lakes with names like Whaley, Morgan, and Johnson. These oxbows are critically important spawning grounds for many fish.

The 137-mile Altamaha River is one of the great natural treasures of the eastern United States. Pronounced Al’ta’mahaw’ the river starts at the confluence of the Ocmulgee and the Oconee Rivers near Hazelhurst and flows undammed to the Atlantic Ocean in Darien. Crossed by roads only five times, the largely undisturbed river is believed to be more than 20 million years old, and pumps an average of 100,000 gallons of fresh water into the sea every second, making it the third largest contributor of fresh water along the eastern seaboard. The river at Doctortown Landing near Jesup is a broad, meandering stream, surrounded by cypress, gum, and willow swamps. Set back up to 2 miles from the main channel are ancient bends of the river, isolated by time into curved, oxbow lakes with names like Whaley, Morgan, and Johnson. These oxbows are critically important spawning grounds for many fish.

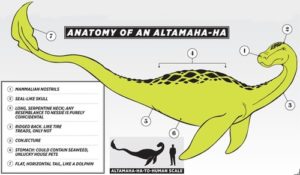

The Altamaha’s watershed (drainage basin) is approximatley 14,000 square miles, qualifying it as one of the largest river basins in the United States. Its northernmost headwaters in the Piedmont province 10 miles NE of Gainseville in Hall County, GA. Including its tributaries (Ocmulgee being the largest) the United States Geological Service records the length of the river at 470miles, and all found within the state of Georgia. According to the USGS, variant and historical names of the Altamaha River include A-lot-amaha, Alatahama, Alatamaha, Allamah, Frederica River, Rio Al Tama, Rio de Talaje, and Talaxe River. There is even the famous Altamahaha….the river monster!

The Altamaha’s watershed (drainage basin) is approximatley 14,000 square miles, qualifying it as one of the largest river basins in the United States. Its northernmost headwaters in the Piedmont province 10 miles NE of Gainseville in Hall County, GA. Including its tributaries (Ocmulgee being the largest) the United States Geological Service records the length of the river at 470miles, and all found within the state of Georgia. According to the USGS, variant and historical names of the Altamaha River include A-lot-amaha, Alatahama, Alatamaha, Allamah, Frederica River, Rio Al Tama, Rio de Talaje, and Talaxe River. There is even the famous Altamahaha….the river monster!

Human History

The Creek, Seminole and possibly Cherokee Indians used the river for fishing, hunting, their main mode of transportation, and the location of many trading posts. The name Altamaha is from an immigrant Yamassee Indian group descended from an interior chiefdom originally known as Altamaha or Tama, located on the Oconee River just below Milledgeville, visited by Hernando de Soto in 1540. The Altamaha chiefdom was forced into slavery, but rebelled and eventually settled in St. Augustine until the Spaniards evacuated the fort headed towards Cuba in 1763. The spanish referred tot he river during the 1600’s as Rio de Santa Isabel, referring to an early mission Santa Isabel de Utinahica, established in the Timucuan chiefdom of Utinahica located at the forks of the river near present-day Lumber City. The ruins of of more than 1,000 Indian sites along the river are evidence of how important the river was, providing transportation and food.

Between 1539 and 1542, when Hernando De Soto visited Georgia, he called this river the Rio De Talaje. He was fascinated by the river and wrote about “Georgia’s Little Amazon” Later, in 1592 a Frenchmen by the name of Jean Ribault sailed from France for Florida skirting the shores of Florida and Georgia sounding the harbors and naming the rivers. He names this river the “Loire” after the longest river in France.

In the late 1700’s through the early 1900’s the river was used for steam boat traffic. These boats hauled staple goods, hardware, and items not otherwise available to upriver farmers and landowners.

During the Civil War the Altamaha River served both the Confederate and Union forces. The Confederates built several forts along the Altamaha, Fort Telfair at Beards Bluff in Tatnall County, and Fort Williamsburg at Upper Sansavilla Bluff, Fort Defense at Doctortown, and Fort James in Wayne County. Fort Barrington witnessed military activity during the American Revolution, the War of 1812, adn the Civil War. At Morgan’s Lake, the Confederate and Union armies faced off in a minor historic episode of Sherman’s march to the sea.

The one major event that happened during the War Between the States was the battle of Doctortown. General Sherman sent two battalions of soldiers to destroy the Doctortown trestle. The bridges at Morgan Lake and Breaker Butler were destroyed. The Union forces were defeated and retreated back to Savannah.

Natural History

The mighty Altamaha river is impressive by volume, but of additional significance are the 170,000 acres of magnificent river swamps that insulate the river almost the entire length of its course. The river, swamps, and sand ridges serve as a refuge to at least 130 species of rare or endangered plants and animals, including seven species of feshwater mussels found nowhere else in the world.

Endangered species such as bald eagles and swallowtail kites soar above its banks. Reptiles such as alligators and a  variety of snakes and turtles use these waters and their banks. Mammals include white-tailed deear, mink, otter, raccoons, rabbits, opossums, and armadillos. Endangered West Indian manatees have been seen swimming as far upstream as Fort Barrington. Fish are plenty and include catfish, sunfish, crappie, bluegill, sturgeon and bass upstream and shad, mullet, striped bass, tarpon, and shark downstream.

variety of snakes and turtles use these waters and their banks. Mammals include white-tailed deear, mink, otter, raccoons, rabbits, opossums, and armadillos. Endangered West Indian manatees have been seen swimming as far upstream as Fort Barrington. Fish are plenty and include catfish, sunfish, crappie, bluegill, sturgeon and bass upstream and shad, mullet, striped bass, tarpon, and shark downstream.

Botanical oddities include the legend of Franklinia alatamaha , a flowering tree that was identified and collected near the river by eighteenth century naturalists John and William Bartram and never seen again. Considered extinct in the wild, only propagated specimens remain. Some believe that the tree may still survive somewhere in the wild near the river. Not only does the river possibly hide the world’s rarest tree, it likely has the oldest trees this side of the Mississippi River. On Lewis Island, a 300-acre tract of virgin cypress contains ancient giants, including one that is believed to be 1,300 years old.

, a flowering tree that was identified and collected near the river by eighteenth century naturalists John and William Bartram and never seen again. Considered extinct in the wild, only propagated specimens remain. Some believe that the tree may still survive somewhere in the wild near the river. Not only does the river possibly hide the world’s rarest tree, it likely has the oldest trees this side of the Mississippi River. On Lewis Island, a 300-acre tract of virgin cypress contains ancient giants, including one that is believed to be 1,300 years old.

The Altamaha and its swamps are more important than just the varieties of species found in them. They play a vitalrole in supporting the rich estuary located downstream. During times of low water, the river swamps accumulate organic matter in the form of leaves, twigs, and other detritus. During spring floods, high water picks up the detritus and washes it into the main river and carries this natural “fertilizer” downstream. The nutrients are trapped and used in the hundreds of miles and thousands of acres of Georgia’s salt marsh. The marsh grasses, primarily Spartina alternaflora, incorporate the natural fertilizer into their stems and roots, and as the marsh grass dies and disintegrates, it is consumed by decomposers of the estuary, such as bacteria and fungi, which help phytoplankton and benthic algae. These ar in turn eaten by primary consumers such as copepods, mud worms ,snails, shrimp, crabs and oysters, which in turn support secondary and tertiary consumers including fish, birds, and mammals. These marshes release their nutrients gradually, creating one of the most productive ecosystems in the world.

The river also carries a tremendous sediment load, adding additional nutrients to barrier islands. Without this input of sediment there might not be a St. Simons Island. Little St. Simons Island continues to grow at a tremundous rate from sand washed down the Altamaha River.

Below Lewis Island, the river forks into different winding channels, and the river becomes affected by twice-daily tides. The vegetation on the riverbanks changes into grasses and reeds, and behind these banks are the remants of antebellum rice plantations such as Butler Island and Hofwyl-Broadfield Plantations. Today Butler island is part of the Altamaha Waterfowl Management Area. The river splits into 4 channels before hitting the sea, from north to south: the Darien, Butler, Champney, and Altamaha Rivers.

The mouth of the Altamaha river is home to ever-changing sand-bar islands that provide food and shelter to multitudes of shorebirds. The American Oystercatcher, Red Knot, Least Tern, Wilson’s Tern, Gull-billed Tern, Brown Pelicans, and Black Skimmer are among many species who depend on isolated barrier-island beaches and sand bars for nesting.

Utilizing the River

The Altamaha River is popular with naturlaists and bird watchers for its flora and fauna, and with anglesrs who pursue its abundant game fish. A watercraft is necessary to experience the Altamaha at its greatest glory. The bird lover will find waterfowl, wading birds, owls, woodpeckers, raptors, and songbirds to be common residents and migrants of the rivers samps, bottomland hardwoods, oxbow lakes, and marshlands.

For more information on river access please refer to our river map, or the Altamaha River Canoe Trail

Information found at Sherpa guides.com